Story of Constantine Lips

|

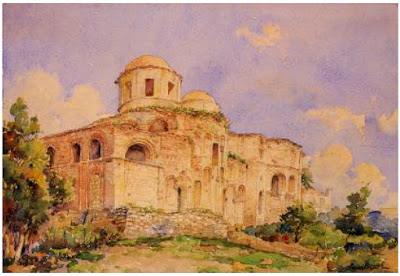

Ali Sami Boyar, "Fenari İsa Mosque", c.1960, The Central Bank of the Republic of Turkey art collection 2042. |

North church of the Constantine Lips Monastery is the earliest surviving cross-in-square planned church in Constantinople. However, Constantine Lips' name was forgotten until the 19th and 20th centuries. The story of the Constantine Lips Monastery Church's discovery and its repairs demonstrates the importance of language in maintaining a culture, and it also shows how a cultural heritage is also lost when a historical structure is used differently than it was intended to be.

There is a Greek inscription surrounding the façade of the northern

church’s apsis walls. Constantinople Patriarch Constantios I was the first

scholar who transcribed and translated this inscription in the 19th

century, and he understood that this church was dedicated to Mary. Patriarch

Constantios I misidentified this church in his book Constantiniade (1846),

because he thought that this was the Panachrantos Church mentioned in

historical resources located near Hagia Sophia. That is why this church was called

at first “St. Mary Panachrantos” (Millingen, 1912).

Two churches make up Fenari sa Camii; the northern church is the older

of the two and is occasionally referred to as Theotokos. Theodora, the dowager

empress and widow of Michael VIII Palaiologos, erected the second church to the

northern structure around the end of the 13th century, and it was devoted to

Saint John.

The southern church’s typicon (foundation document) which

was discovered in Athens in the 17th century, was translated into

French in 1921, and then this church complex named as “Constantine Lips”

(Delehaye, 1921; Talbot, 1992; Thomas and Hero, 2000; Karakaya, 2021).

At the early years of the Turkish Republic, Theodore Macridy, assistant

curator at the Istanbul Archaeological Museum, conducted an excavation in this

church. He moved from Istanbul to Athens in 1931 to serve as the Benaki

Museum's director, but he passed away in 1940. Cyril Mango later released

Macridy's report on this church in 1964.

Macridy did some restorations and remove the plaster from both the

interior and exterior walls. In 1960, after a minor restoration of Evkaf, an

extensive restoration project was carried out by Byzantine Institute of

America. The reports of this restoration published respectively in 1963 and

1968.

The northern church was the subject of Greek scholar Vasileios Marinis'

PhD thesis at the University of Illinois in 2004. His thesis is the most

in-depth study of this structure.

The Greek inscription from the 10th century that surrounds the northern

church's apsis façade is the most significant feature of the northern building.

According to Spingou (2012), this inscription's writing style is extremely

complex and could only be understood by the most educated members of the

Byzantine empire in the tenth century. Semavi Eyice further emphasizes the

significance of this inscription because it makes it very evident that someone

by the name of Constantine dedicated this church to Mary.

The Greek used in this inscription is from the Middle Byzantine period.

However, the palmette motifs of the Constantine Lips Monastery's north church

come in a variety of shapes and styles that are not Byzantine in style but

rather quite reminiscent of ancient patterns.

According to Marinis (2004), recycled materials were used in the

decorating of the north church, including recurved antique slabs for the

cornices and pilaster capitals. According to Mango and Hawkins (1968), the

initial location of these recycled materials was Cyzicus (Mysia, Balkesir).

The story of the North Church’s discovery demonstrates the necessity to

view historical sites as both architecturally significant landmarks and sources

of literature and visual culture.

And the most crucial element for maintaining a culture is language. The Greek population in Istanbul spoke the same language as their Byzantine ancestors, but nobody could read a Byzantine inscription from the 10th century until the 19th century because Byzantine culture has been completely lost. This is similar to how the name of Constantine Lips was lost until the 19th and 20th centuries.

Even though the architecture survives, when a language is lost, a culture inevitably disappears.

Bibliography:

Delahaye, H. (1921). Deux typica byzantins de l'époque des Paléologues. Bruxelles,

M. Lamertin.

Karakaya, E. (2021). Kuruluş Vakfiyesi ve Arkeolojik Belgelerin Işığında

Bir İmparatorluk Medfeni-Lips Manastırı. In M. Kurtoğlu (ed.). Fenari İsa

Camii Koruma ve Restorasyon 2013-2018. İstanbul, T.C. Vakıflar Genel

Müdürlüğü ve Yılmaz Yapı, p.15-32.

Macridy, T. (1964). The Monastery of Lips (Fenari Isa Camii) at

Istanbul. Dumbarton Oaks Papers, 18, p. 249-277.

Mango, C., & Ernest J. W. Hawkins. (1968). Additional Finds at

Fenari Isa Camii, Istanbul. Dumbarton Oaks Papers, 22, p. 177–184.

Marinis, V. (2004). The Monastery Tou Libos Architecture, Sculpture, and

Liturgical Planning in Middle and Late Byzantine Constantinople [PhD thesis in

Art History, University of Illinois] Illinois Library. https://www.ideals.illinois.edu/items/88652

Millingen, A.V. (1912). Byzantine Churches of Constantinople.

London, Macmillian.

Spingou, F. (2012). Revisiting Lips Monastery. The Inscription at

the Theotokos Church Once Again. The Byzantinist, p. 16–19.

Talbot, A.-M. (1992). Empress Theodora Palaiologina, Wife of Michael

VIII. Dumbarton Oaks Papers, 46, p. 295–303. https://doi.org/10.2307/1291662

Thomas, J.P. Hero, A.C. (2000). Byzantine Monastic Foundation Documents: A Complete Translation of the Surviving Founders’ Typika and Testaments. Washington, DC: Dumbarton Oaks, Trustees for Harvard University.